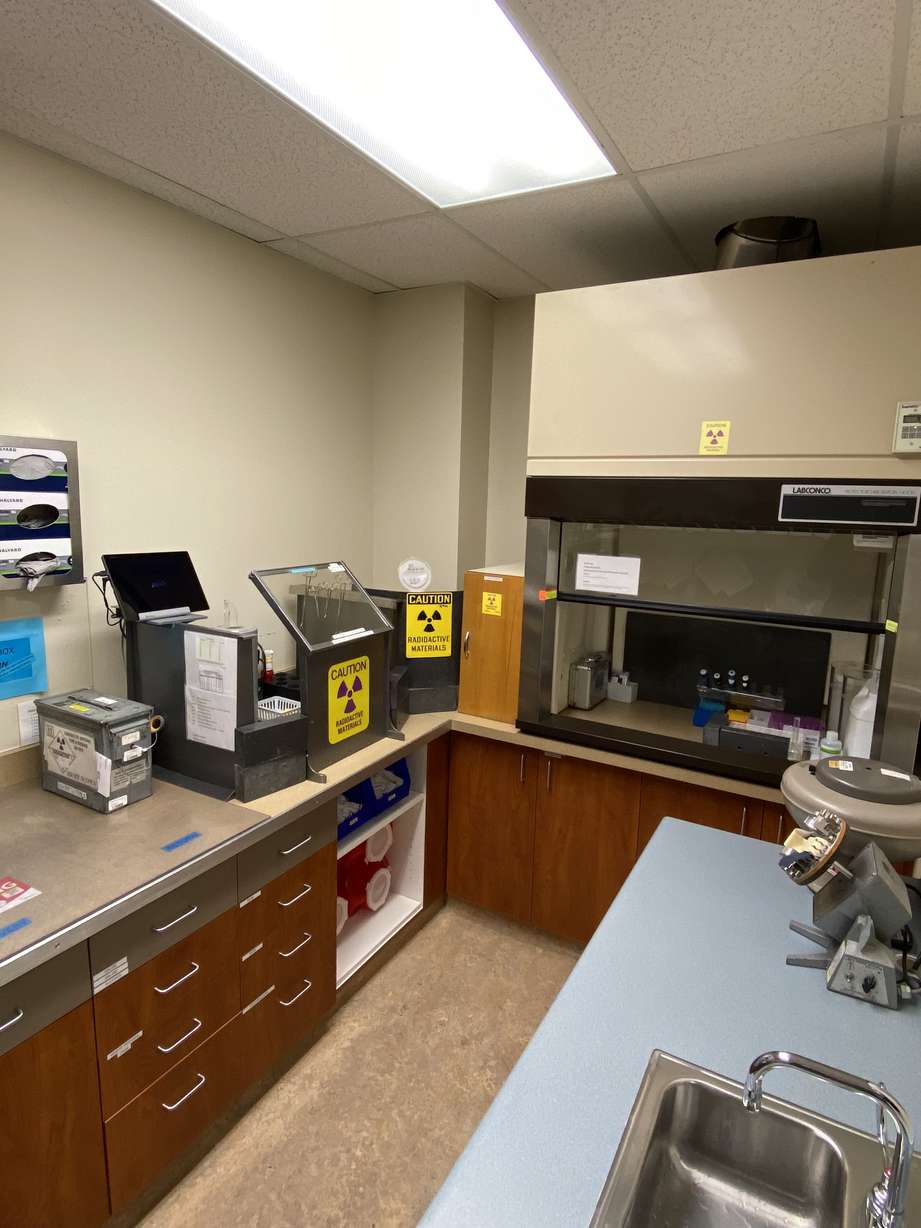

A bottle of multiple doses of radioactive iodine with a pill containing one dose. Radioactive iodine is used to treat thyroid cancers and diseases. (University of Utah Health)

Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

SALT LAKE CITY — Shirley Crepeaux was a little hesitant when doctors proposed radioactive iodine as a treatment for her thyroid cancer about 12 years ago. She trusted her doctors at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, but she was still terrified and afraid.

“When faced with leaving a 12-year-old alone and my husband a widower or drinking some poison, I’ll drink some poison,” she said.

Crepeaux, now 54, is mom to four children. When she was diagnosed with cancer, her youngest was 12.

“We tried to make the cancer diagnosis a big nonevent as much as we possibly could,” she said.

The radioactive iodine treatment, however, was definitely an event.

She was given a tiny vial to drink while alone in a specific room and was given a lot of warnings through a speaker system telling her not to spill it or drop it. She said it tasted salty.

After drinking it, she was told to stay away from pregnant people and children for a week. She spent a week in her bedroom. Crepeaux said it was “pretty miserable,” but her husband did what he could to help her stay in contact with the family, including video calls to the breakfast table and waves through the window.

“In the big scheme of things, it was a week out of my life and then I was back to being myself,” she said.

How it works

Thyroid cancer is one of the more common cancers, and one of the easiest to treat — partially due to radioactive iodine.

Dr. Dev Abraham at the Huntsman Cancer Institute said radioactive iodine was first used in the 1930s and 1940s, around the same time chemotherapy was being developed, and the treatment became popular in the 1960s. It treats thyroid cancers and disorders and Graves’ disease, which causes the thyroid to overproduce hormones.

“It’s stood the test of time,” Abraham said.

What has changed throughout the time it has been used is the dosage, Abraham said there have been more reports recently showing a small but statistically significant increase showing too much radioactive iodine can cause a higher risk of other cancers, causing dosages to be brought down in the last five to 10 years.

Radioactive iodine is administered in a capsule or drink, and Abraham said it is a unique targeted treatment. Thyroid tissues, including tissue from thyroid cancer that has spread throughout the body, will be destroyed by the treatment once it enters the cell. Other cells that come in contact with the radioactive iodine in the blood won’t be affected.

“It is a treatment that is specifically determined by the ability of the tissue to uptake, or pick up, or trap iodine. So iodine trapping tissues are specifically susceptible to being killed by this low-grade radioactivity,” Abraham said.

Before taking a dose of radioactive iodine, doctors like Abraham will help a patient starve their thyroid and thyroid cancer tissues from iodine by avoiding certain foods to make it so those cells are hungry and will absorb more of the radioactive iodine.

Most often, the treatment is used after much of the cancer is removed in surgery to address leftover thyroid tissue that could have cancer cells or cancer cells that have spread, something that is more common in thyroid cancers than in many other cancers.

He said in many cancers, spread to other areas leads to a worse prognosis. But with radioactive iodine, spread of thyroid cancer does not necessarily mean a worse prognosis.

Long-term effects

Abraham said although one death is too many, there are not very many patients who die from thyroid cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates there have been about 43,800 new cases of thyroid cancer in 2022 and about 2,230 deaths.

The main goal of radioactive iodine is to reduce the frequency of recurrence of thyroid cancer, he said.

Crepeaux continues to have appointments with Abraham every year, he said he has cared for her for years and that it seems she will continue to do very well and the radioactive iodine treatment was effective.

Crepeaux is one of few thyroid cancer patients who have residual disease, small amounts of cancer left behind that do not grow. Abraham said these are probably dying thyroid cancer cells, and in most patients, cancer cells remaining but not progressing is as good as a cure.

Because of the radioactive iodine treatment, Crepeaux is constantly dealing with a dry nose, throat and eyes. She said she always has her water bottle with her and uses products to help add moisture.

Abraham said this is one of the reasons treatment should be tailored to the patient, using the smallest effective dose. He said two doses are sometimes used in severe cases, but rarely three.

If the cancer did come back and Crepeaux were to decide to have a second dose of radioactive iodine, she said it would lead to her having no tears, spit or saliva — even more discomfort.

Optimism

Crepeaux was a hairdresser for 30 years, but now she is in school to become a medical assistant.

“This is something that happened to me. It’s not who I am. I’m Shirley and I’ll always be Shirley. A little salty. A little raunchy. … I don’t take guff from anybody. And if I love you, I love you with everything. … I won’t let cancer or anything else change that or define me,” she said.

She said it’s thanks to her primary physician that she got screened for thyroid cancer. If she hadn’t, she could have died within a few years. When it was found, it was between stage three and four and had already spread into her lungs. Her only symptom up to that point had been shoulder pain and difficulty swallowing.

Now, Crepeaux encourages everyone to feel for lumps on their thyroids doing self-checks, or ask their doctor to do a check during a yearly physical.

Crepeaux was told after her surgery she would have a very whispery, raspy voice, but therapy and her loud voice helped save her voice — although she said it takes a lot more effort now to produce an audible voice.

“Fortunately, I was one of those people with an abrasively loud voice prior to the surgery, so now I just have a normal voice,” she said.

Her laugh, however, is still the same loud laugh, a laugh that brings in more laughs from others in the room.

Overall, Crepeaux shared a message that there is hope and encouraged others going through similar situations to be grateful and focus on the little things that bring them happiness.

“Most people with cancer are living with it, they’re not dying with it,” she said.